Sunday Best

Laundry and ironing were arguably the most arduous of household tasks through the 1800s, and into the early 1900s. But presenting herself and her family as tidy and well-groomed—especially on Sundays—was a matter of pride for the housewife of those times. Clean and neat equaled respectability.

Rachel Haskell, in a diary entry for March 1867, called doing the laundry “the Herculean task which women all dread” and “the great domestic dread of the household.”

Starched white aprons and petticoats, ribbons and bows, seem like a dubious choice for frontier apparel, but to pioneer women they represented victory over harsh environments; order; and preservation of feminine roles.

Traveling the emigrant trails to California and Oregon, women washed clothes and linens whenever possible in an effort to maintain a link to “civilization.” Riverbanks might be lined with women and their wash tubs, buckets, pots, washboards and mounds of dirty laundry. Women’s diaries even note ironing clothes when wagon trains stopped on the trail.

Tennessee Valley Authority, Circa 1930s

“Oh such work, and such a lot of dirty & old clothes not scarcely fit to wash… . I got them ready for the line, the wind so hard, yet I managed to hang all out. The tub frozen full of water, I worked at 2 hours before I could get enough of it out so I could put the clothes in.” -Emily French, Entry in her diary for January 8, 1890

“Oh! Horrors how shall I express it; it is the dreded washing day…but washing must be done and procrastination won’t do it for me.” -America E. Rollins Diary entry from her overland journey to Oregon in 1852

Soap maker; Frank Hohenberger, photographer. A lye solution and rendered animal fat were boiled together. It was a multi-day process.

Before homes had indoor plumbing, buckets of clean water had to be hauled (mainly by women) to the house for cooking, washing dishes, bathing, laundry and cleaning. Then the “slops” had to be hauled back outside the house and dumped. The spring, creek, pump, well, or street hydrant might be 60 yards downhill in an unbearably hot summer, or frozen in winter. One wash, boiling, and rinse of clothing used about 50 gallons—or 400 pounds—of water.

Indoor plumbing remained a matter of class well into the 20th century. The rich got it before the poor; the city dweller got it before the farmer.

Greene County, Georgia; tenant farm; July 1937; Dorothea Lange, photographer

To Those Plucky Housewives…

TO THOSE PLUCKY HOUSEWIVES WHO MASTER THEIR WORK INSTEAD OF ALLOWING IT TO MASTER THEM, THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED.; Practical Housekeeping: A Careful Compilation of Tried and Approved Recipes; 1883.

“Washed and put out the white clothes but it rained and I hung the colored ones in the house.” -Mary Jane Hunt, Newbury Park pioneer whose diary carefully notes on every Monday in 1896 whether or not she did the laundry that day

By the mid-1800s, most white women in the United States could read and write. The plethora of domestic advice manuals sought to teach moral values through good housekeeping; an untidy home led to frequenting the saloons. Housewives were advised to keep to a strict weekly schedule for their chores:

Wash on Monday, iron on Tuesday, mend on Wednesday, churn on Thursday, clean on Friday, bake on Saturday.

With no ready-made laundry products on store shelves, women had to know how to make their own recipes for cleaners and starches using ingredients such as saltpeter, borax, vinegar, eggshells, baking soda, lemon juice, ammonia, beef’s gall. Fabrics and dyes of the period necessitated a different recipe for each fabric and stain.

Housewifery was terribly hard and demoralizing work. Authors of domestic manuals tried to provide a road map for new brides and buck up their spirits. Miss Catherine Beecher wrote in 1848: “The number of young women whose health is crushed, ere the first few years of married life are past, would seem incredible to one who has not investigated this subject…”

Pressing Issues

Wearing ever more complicated pieces of apparel (that required a great deal of skill to sew and care for) was one way for the middle- and upper- classes to demonstrate their elevated place in the social hierarchy.

“Laundresses must be early at their work…” Some washerwomen (who did only wash) and laundresses (who also ironed, and cared for fine, elaborate articles) did laundry and ironing in their employers’ houses, thus avoiding the expense of purchasing supplies. Others took wash into their own homes, which allowed them to care for their children at the same time. “Getting up the laundry" was so much work, and a chore so hated, that laundry was sent out by all who could afford it.

With no public assistance to fall back on in the 1800s and early 1900s, taking in wash provided a crucial means of support for widows and divorcees, and an important supplement to a working class family’s income.

Both the Union and Confederate armies hired laundresses during the Civil War. A laundress traveled with, and was sometimes captured with, her regiment. She was given housing, food, fuel, and medical care; a soldier paid her 50¢ to do his wash. In her "free time" she often assisted the doctor with wounded and sick men. "Suds Row", where the laundresses worked and lived, was off-limits to the rest of the camp. Civil War laundresses were white and black (both free and enslaved), they were Native American women, sometimes men who were slaves, or soldiers who washed other soldiers’ clothes to make money. Often they were wives of soldiers.

Dressmaker Sarah Boone invented an ironing board to make pressing sleeves and bodices easier. Her patent was granted in 1892.

American Ingenuity

The late 1800s and early 1900s are sometimes called America’s Golden Age of Invention. It was a period of intense competition for patent rights to new devices, and ideas were coming fast and furious. Some were practical, some not so much. But all had the potential for financial reward.

Many inventors were ordinary American citizens, including women and African Americans. The cost of obtaining a U.S. patent was inexpensive and the application process was easy. In 1880 the average time between applying for and granting of a patent was only 170 days. An inventor mailed documents to the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C. or hired a patent lawyer to manage the patent process.

Inventress Florence Potts received at least four patents, her first in 1871 at age nineteen. Her “Cold Handle Sad Iron”, one of the most popular irons produced well into the 1900s, was manufactured throughout the world.

Both women and men patented designs for time- and labor-saving gadgets to ease the back-breaking labor of washday. Manufacturers advertised the new tools’ abilities to extend the user’s lifespan, erase wrinkles, and preserve a delicate woman’s health. Oh, and save money, too.

By the end of the 1800s, housewives and washer women could purchase mass-produced boiling tubs, washboards, wringers, mangles, irons of all shapes and sizes, clotheslines, and laundry soap from catalogues and corner stores.

MECHANIZATION IMPROVES PRODUCTIVITY: Fluting Machines

In the mid-to-late decades of the 1800s, pleated frills (or fluting) were the thing. They were used on men’s, ladies’ and children’s clothing as well as bedspreads, bed canopies and curtains. Fluting and goffering irons were heated over a flame and produced one frill at a time, an agonizingly slow businesss.

The fluting machine could produce numerous identical pleats very rapidly, a time- and labor-saving device welcomed by dressmakers, laundresses, and homemakers. Heated slugs were placed in the hollow cylinders. Rollers adjusted to accommodate different thicknesses of material.

In the mid-to-late decades of the 1800s, pleated frills (or fluting) were the thing. They were used on men’s, ladies’ and children’s clothing as well as bedspreads, bed canopies and curtains. Fluting and goffering irons were heated over a flame and produced one frill at a time, an agonizingly slow businesss.

The fluting machine could produce numerous identical pleats very rapidly, a time- and labor-saving device welcomed by dressmakers, laundresses, and homemakers. Heated slugs were placed in the hollow cylinders. Rollers adjusted to accommodate different thicknesses of material.

THE AGE OF ELECTRICITY

Edison. Tesla. Westinghouse. Bell. The men who harnessed electrical power believed they held the key to the world’s future.

Thomas Edison patented his incandescent light bulb in 1880, but electricity was new and mysterious and frightening, and it took a long time for people to bring it into their homes:

Installing the network of wires was difficult and expensive.

Retrofitting existing homes and bringing power to rural areas was costly.

Less than 10% of farm families had electricity in the 1920s. In 1922 80% of the nation’s homes had no electricity or, at best, wiring for just minimal illumination.

Until the 1930s most new homes were wired only for lights. One or two small appliances could be used on their house light lines.

The market for domestic electricity was divided into (lower- and middle-income) homes with illumination only, and (upper-income) homes wired for full service.

And electricity was very dangerous – newspapers were full of stories about people and livestock who were electrocuted in the early days. Change came in the 1930s, when New Deal policies set a minimal standard of electrical modernization for American homes -it was a matter of social justice.

The Contest for Best Iron Heats Up

Carpenter Electric Tailor’s Goose; photo from VintageElectricIrons.com

The first electric flatiron was designed and patented in 1882 by Henry W. Seely from New York. His iron used carbon sticks to produce heat. Instead of a cord, it had detachable wires connecting the iron to an electric circuit. The iron’s awkward design makes it unlikely that any were actually sold.

Enter Charles E. Carpenter, who invented the first electric flatiron known to actually be manufactured for use. Carpenter received his first patent for an electrically heated flat surface in 1889, when he was 25 and a student at the University of Minnesota. Acting on suggestions from F.W. Nevens, Carpenter designed a clothes iron. His iron used zig-zagged iron wire to conduct electricity and produce heat. They formed the Carpenter-Nevens Electro Heating Co., which produced electric tailor’s irons as early as 1890.

Four of the irons were first used in Mr. Nevens’ clothing business, then more were installed at the Hennepin Steam Laundries in Minneapolis. By 1893 the company had a catalogue of 16 pressing and heating devices for sale, which could “be used on any electric light wire…” .

Power to the People

For the first 20 or so years, power companies generated electricity for only a few hours during the evenings—their focus was mainly on its use for lighting.

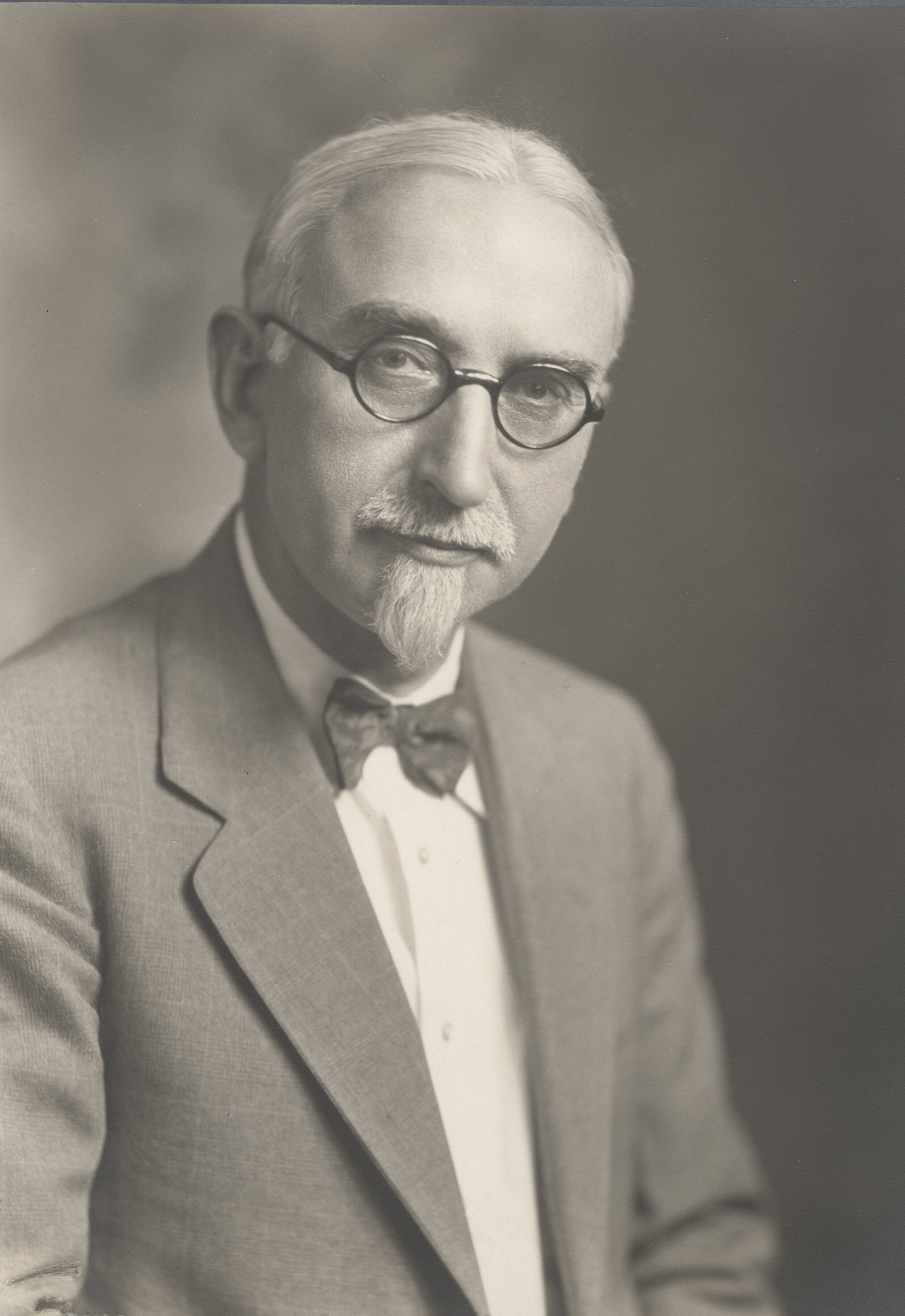

Earl H. Richardson, photo courtesy of the Robert E. Ellingwood Model Colony History Room, Ontario City Library.

In 1903, Earl H. Richardson was a superintendent for the Ontario Electric Company (OEC) in Ontario, California. He had been experimenting with designs for an electric iron, figuring if women began to use electric irons the demand for electricity would increase, and OEC could operate around the clock. Richardson handed out several dozen samples of his iron to OEC consumers, and then persuaded his company to generate power during the day every Tuesday (ironing day). It worked.

But customers complained that the iron got too hot in the center. Richardson’s wife suggested he design another iron with more heat in the point to press around buttonholes, ruffles and pleats. Customers loved “the iron with the hot point”.

Thus the Hotpoint trademark was born, and in 1904 Richardson founded the Pacific Electric Heating Company, renaming it Hotpoint Electric Heating Company in 1907. In 1920 over 800,000 Hotpoint irons were sold around the world.

By the late 1920s the flatiron and light bulb were the electrical devices most widely found in electrified households. Manufacturers introduced electric washing machines in the early 1920s, but few consumers bought them.

Let the Laundry Do It!

Commercial “steam laundries” emerged in the mid-1800s, but took off as an industry in the 1880s, with an accompanying plethora of trade journals, associations, suppliers, engineers, and an international trade in laundry equipment. Owning a steam laundry became a fashionable endeavor, often bringing in a comfortable living if not a fortune, and entrepreneurs thought the trade would be easy to learn. Not so. Owners and workers dealt with complicated machinery, sometimes with only the vaguest idea of how to operate it.

Commercial laundries were a substantial source of employment for women, who made up most of the workforce. But the businesses were predominantly owned and run by men. Between 1860 and 1890, the number of laundry workers in the United States jumped from 38,633 to 246,739.

“With all due respect to the fair sex, real progress only began after businessmen began to see the potentialities in the business and to invest both their money and their brains therein.” —Words of wisdom from an American laundryman

Women starchers and ironers were considered skilled workers and earned comparatively high wages. When ironing and starching machines were introduced, those skilled workers were transformed into easily replaced, lower-paid machine tenders.

Families, rich and poor, sent at least part of their laundry out for someone else to do. Initially, commercial laundries took in mainly “starch work” or “bachelor’s bundles” (men’s shirts, collars and cuffs) and industrial work from hotels and ships. As equipment became more sophisticated, they offered a full “family wash” and cheaper partial services. In the first decades of the 1900s, the city of Oxnard offered at least one Chinese laundry, a steam laundry that also sold fuel oil and soft water, a French laundry, and a hand laundry that also provided baths (for people).

After WWII, when automatic washing machines and dryers were readily available and most homes were electrified, commercial laundries began to disappear and “getting up the wash” once again became the housewife’s chore.

CELESTIAL LAUNDRIES

By 1891, the small hamlet of Timberville that grew up around the Conejo Hotel boasted not only a post office, a blacksmith shop, and the Timber School, but a Chinese laundry as well.

During the Gold Rush there weren’t many women available out West to do laundry. Since white men considered “women’s work” beneath them, many shipped their dirty clothes to Hong Kong. The charge per dozen shirts was $12 (cheaper than shipping it back East). It took four months for clean laundry to make its way back.

Racist hostility made it almost impossible for Chinese immigrants to work in the gold mines or the timber and fishing industries in California. Recognizing a much-needed business opportunity, a Chinese entrepreneur in San Francisco named Wah Lee opened the first known Chinese laundry in 1851. He charged $5 to wash a dozen shirts.

Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 14 May 1870

“Many local people patronized these...celestial laundries, their business was gigantic, in fact, they were an institution in the town.

There was always four to six "pig tails" employed in each institution and both turned out perfectly beautiful laundry at a very nominal sum, ...they worked 12 to 15 hours per day...It was great fun to...watch them iron with their gigantic irons; first they would spread out the garment on the board, take a sip of water from a bowl and spew this water in a fine spray all over the piece...and then proceed with the ironing, at the same time keeping up a string of conversation in Chinese sing song...Their work, their customs, their language, in fact their whole ensemble, fascinated us small boys...” -Dr. William C. Shipley, Tales of Sonoma County, 1938

By the early 1900s, Chinese laundries could be found in virtually every town throughout the U.S.

Getting Up The Laundry

Photograph by Clifton Johnson

Sort your clothes and linens by color, fabric, and degree of soil; haul water; heat it; and fill the tubs for soaking. Do this on Sunday, or late Saturday to preserve Sunday as a day of rest. Make sure you’ve chopped enough wood for the tasks.

On Monday morning, drain off that water, heat another batch, and pour hot suds on the finest clothes. Wring them out, and repeat the process.

Wash each article in that suds bath, rubbing it against the washboard.

Wring them out again.

Rub soap on the most soiled spots, then cover them with water in the boiler (on the fire or the stove) and “boil them up.” Agitate with the wash-stick.

Take them out of the boiler and rub dirty spots again.

Rinse in plain water.

Wring again.

Rinse again in water with bluing.

Wring very dry.

Make up your starch recipe. Dip the articles to be stiffened in it.

Wring once more.

Load them up and carry them to the line and hang up to dry. Don’t forget to clean the clothesline first. Or spread the wash on the grass or over bushes to dry. If it’s raining, hang them inside in the kitchen over the fireplace.

While that load is drying, repeat the entire process on progressively coarser and dirtier loads of clothes.

Take down the dry clothes and bring them in for folding and ironing. Clean the clothes pegs. Clean the wash buckets.

On Tuesday, get ready to iron. Sprinkle the dry clothes with your hand or a wet whisk-broom.

Roll them in a cloth and let sit for one to twelve hours.

Heat three to six irons, each rubbed with beeswax and free from cinders and ashes.

If the handles are iron, wrap them in a cotton cloth to avoid burning your hand. Don’t use wool – smells bad when burnt.

Try each iron before use on a piece of paper or spare cloth to make sure it won’t scorch the clothes.

Proceed to iron everything, including sheets and pillowcases, working close to a hot fire or stove even in summer, using irons that might weigh eight or ten pounds each. As the iron cools, replace with a hot one from the stove.

Hang the damp, freshly starched and ironed clothes to dry again and take a rest.

Make sure you set aside some days every few months or so to make your own soap.

We’ve come a long way, baby!

© 2019 Kathleen E. Boone